|

| Add caption |

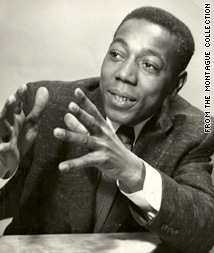

Montague -- Magnificent

Montague, as he's been known since his days as a pioneering radio DJ --

amassed an 8,000-piece collection reflecting names from the well-known

to the forgotten to those history never thought to remember. It's valued

in the millions; some call it priceless. One assessment of just five of

the pieces puts the total value of those treasures alone somewhere

between $592,000 and $940,000.

"I shudder to even fantasize what it could go for," said appraiser Philip Merrill, who performed the assessment.

For decades Montague

carted the collection of African-American artwork, artifacts and

ephemera around the country with his family as he took jobs at radio

stations in New York, Chicago, Oakland, and Los Angeles, and then

finally to Las Vegas, where he moved 12 years ago after closing a

station he built from the ground up in Palm Springs, California.

The Montague Collection was his prized possession, but because of financial woes he has lost it. It is now up for auction.

"I have not been able to

maintain the collection for the last couple of years," Montague said.

While working with his wife of 56 years, Rose Casalan, to archive and

prepare the collection for sale, he took out a loan to help pay for the

archiving, found himself overextended financially and declared

bankruptcy. His collection was seized, and it is now in the hands of a

trusteeship charged with selling it to satisfy his debts, including a

judgment for $325,000 plus interest and court fees.

If no one steps up to buy

the collection in its entirety, Montague's life's work could be

dismantled and sold off in pieces to pay his creditors.

In the meantime, it is stored in a confidential location in Nevada.

Boxed and hidden under

tight security in Las Vegas -- away from the city's bright lights and

infamous Strip -- is the item that sparked his collection: a set of

first-edition Paul Laurence Dunbar books Montague purchased in

Washington in 1956.

"One day I stumbled into

a book by Paul Laurence Dunbar," he said. Until that day, he had never

thought of collecting memorabilia -- much less heard of Dunbar, author

of novels, short stories and essays, and the first African-American to

gain national acclaim as a poet.

"I bought the book, and I never looked back after that," Montague said.

It was the first time he

saw the "Negro dialect" Dunbar was known for using in his early poetry,

and it sparked his interest in African-American culture -- "the Negro

problem," as it was called in periodicals in the 1950s.

"I began to learn who

some of the blacks were in the 1800s and 1700s, and I was shocked. I

said, 'Well, I have to do something about this.' So I started going to

bookshops and visiting the dealers. And I would ask, 'Do you have

anything black? Negro?'"

He looked for first

editions and signed copies, no matter the cost. "I just had to have it,"

he said. "I had to bid my brains out."

He dug through magazine

crates and traveled the country visiting rare book stores and auctions.

He once traveled from Los Angeles to Germany to purchase "The African,"

an 1890 pastel drawing of an African king wearing traditional robes. It

was drawn and signed by Austrian artist Rudolf von Mehoffer, who was

known for his portraits of German and Austrian royalty.

"I would spend sometimes

a day, hours, in a place going through old magazines, looking for

something about the Negro. Something about the word 'colored.' Something

about the word 'black,'" he said.

"I didn't collect; I

chased," he said, making investments in time, money and energy that he

says he cannot measure. "I was not writing history; I was chasing it."

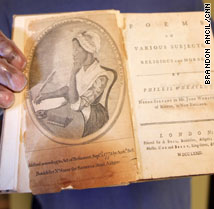

For more than 50 years

he memorized names of writers, artists and filmmakers, hunted them,

found them, and added their works to his collection. There are pieces

that inspire him, like the first edition of Phillis Wheatley's "Poems on

Various Subjects," dated 1773 and signed by the author, who was born a

slave and became the first African-American to have a published book.

There's a 1944 Fred Sapp oil painting of Toussaint L'Ouverture, leader of the rebellion that emancipated Haiti's slaves in 1801.

He also has pieces he

considers historical yet repugnant, such as sheet music to the 1900 song

"Coon, Coon, Coon" and a 1935 advertisement for "The World's Only

Flying Negro Singers."

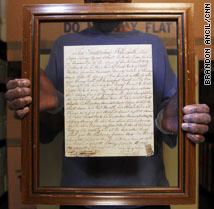

Also secured in the Las

Vegas vault is a fundraising letter Booker T. Washington wrote seeking

financial assistance for 221 students at Tuskegee, the college he

founded in 1881. There are photographs, receipts and letters from the

Lincoln Motion Picture Co., the nation's first all-black production

company. Brothers George and Noble Johnson operated it from 1916 to

1923, producing five full-length films and other works they showed

mainly in black churches and small assembly halls.

Montague acquired a copy

of the Liberator, an anti-slavery newspaper published from 1831 to

1865, when the Civil War ended and the 13th Amendment was ratified,

abolishing slavery.

There's the 1820 bill of

sale for "Two Negro boys George + Paris," who were sold for a total of

$1,230, and a contract with Negro Nancy, who with an "X" and a

thumbprint agreed to a life of indentured servitude in Pennsylvania.

"I'd say I have 500 to

600 items that the public have never seen and will never see until they

see the collection," Montague said, including memorabilia and recordings

from his time as a DJ and radio station owner, where he recited poetry

with soul music pioneer Sam Cooke, performed with R&B artist Wilson

Pickett and coined the phrase, "Burn, Baby, Burn."

Montague says he came up

with the phrase in 1962 while working at a station in New York. He was

given a copy of Pickett's new song, "If You Need Me," and he fell in

love with it.

It was a custom to say "buuurn" when music was moving.

"Something hit me, and I

said, 'Burn, Baby, Burn,'" Montague said. Then he asked his listeners

to call in and experience it with him.

"If you like the record, call me and say, 'Montague, Burn, Baby, Burn.'"

That night a catchphrase

was born. Students would call in with their name and their school and

say "Burn, Baby, Burn" to express their pleasure with the R&B and

soul hits he was spinning. They'd howl and he'd drop the latest album by

the Platters, Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder -- "All the heavyweights,

baby" -- and together they'd exclaim, "Buuurn."

Magnificent Montague

took his show -- and his hot catchphrase -- from New York to Chicago,

and from Chicago to Los Angeles, where he arrived three months before

the August 1965 Watts riots.

By then, "Burn, Baby,

Burn" had caught on in Los Angeles and quickly became the battle cry for

those taking to the streets after a white highway patrolman arrested a

black motorist on suspicion of drunken driving. It was a hot night in

the Watts neighborhood, and the scene soon escalated into a

confrontation between police and nearby residents. Tensions between the

black community and police boiled over, and a week later 34 people were

dead and more than 1,000 were injured. More than 600 buildings were

damaged or destroyed.

"They wanted to be

recognized," Montague said of the rioters. "And the only way they could

be recognized with what was going on in Watts, what happened with this

young man, what happened with no jobs, all of this grief, the easiest

thing to use is what they knew how to use."

He stopped using the phrase after that, but he kept the recordings and added them to his collection.

Merrill, who assessed the collection, calls him a hero.

The collection was built on love ... I was drunk with the passion to collect.

Nathaniel "Magnificent" Montague

Nathaniel "Magnificent" Montague

"You're not going to see

another collection like this," said Merrill, who is an appraiser on

PBS's "Antiques Roadshow" and a consultant for the Smithsonian National

Museum of African-American History and Culture.

"Sometimes you find mass-produced pieces," like posters, brochures or pamphlets, Merrill said. "This is not that. It's all rare and one-of-a-kind.

"The collection was built on love," Merrill said. "He did this for future generations."

For 50 years Montague

kept his pieces in public storage facilities, protected by nothing but a

padlock. It was set up as his personal museum. Paintings and documents

were framed and hung. Books and periodicals were meticulously organized.

He kept a small desk and chair in the storage bin and spent time with

the collection every day, reading and researching.

"No one knew where it

was," Montague said. "It had no address. Nobody knew nothing. Not even

the storage people knew what I had."

When it was time for him

to move to a new city, he'd find a new home for his family and a new

home for his collection. He'd drive behind the movers and keep an eye on

it.

"When I first started

collecting, I had no plan," Montague said. "I was drunk with the passion

to collect. I had no plan to do anything with it but keep it. To hoard

it for myself. Have it in my house. It was for me. I was doing it for

Magnificent Montague."

Eventually he decided it

was something that needed to be shared. He saw "museum libraries" on

trips to Europe, places where artifacts could be viewed and touched but

not checked out. He wanted to do the same with his collection.

"I'd like to see it

where the people of America -- the young people mainly -- can have

access to it, where it can be toured if possible," he said.

I had no plan to do anything with it but keep it. To hoard it for myself.

Nathaniel "Magnificent" Montague

Nathaniel "Magnificent" Montague

He didn't get a chance

to finish his work. After the judgment against him was filed, he

declared bankruptcy in August 2011, and the collection was seized in

October.

"It's an emotional

case," said Dotan Melech, the federal bankruptcy trustee assigned to

administer the estate. "The conventional approach to bankruptcy is to

take the few items that were worth anything, sell it and satisfy the

debt, and give the debtor the rest of the items. That's the conventional

approach to bankruptcy. That's what any bankruptcy trustee would've

done."

However after meeting Montague, Melech said he caught his passion. "It's very contagious," he said.

"This is an opportunity

to do something that can really benefit future generations and educate

for many years to come, and I share the same desire and objective as the

debtor has in this case," Melech said.

"I feel that this is an opportunity for the bankruptcy system to do the right thing."

He is looking for what he calls a win-win situation, where the debt can be satisfied and the collection can remain intact.

Merrill, a collector himself, is worried that won't happen.

"It's like a basketball game, and we're in the fourth quarter," he said.

The trusteeship has

targeted universities, museums and collectors as potential buyers, but

so far no one has moved forward. The next step may be selling it in

pieces. Eventually the debt must be settled.

For now, the Montague Collection remains intact and out of sight. Montague misses it.

CNN recently was granted

access to the collection on the condition that the location and other

details of the storage facility would not be disclosed. Montague was

able to visit it, as well. With the exception of a few items -- Phillis

Wheatley's book, Negro Nancy's contract, and a pincushion crafted by

Patrick Reason -- all he was able to touch were the boxes.

He was satisfied, even chuckling at how he nearly didn't purchase the pincushion from a shop in Florida.

"This lady, she has this

little pincushion. I say, 'What do I want with a pincushion?' and she

says, 'Oh, you want this one. This one I think is important,'" he

recalled.

He bought it, and later

while thumbing through his history books came across Reason, a freeborn

black abolitionist who expressed his anti-slavery sentiments through

art.

The pincushion --

engraved with an image and the words "Black Man Kneeling in Chains" --

was sold by white abolitionists as a fundraiser.

"It's in good hands,"

Montague said of the piece and his collection. He speaks of it as if the

only potential outcome is what he longs for, that it will stay

together.

"They are able to do for it ... and present it and get it sold," he said, rubbing the boxes.

He says he has no regrets, and he sounds hopeful.

"If tomorrow it was said

to me, 'Take it back; take it back; take it back. Everything is all

right, take it back,' I would turn it down," he said.

"I can't do it justice.

I've done my thing, and I've done it from my heart and soul. Now it

deserves better than me. The hurt is surpassed by where it is going to

go, and what it is going to be."

Meanwhile, Melech continues to search for a buyer who will keep it intact so it won't have to be sold piecemeal.

No comments:

Post a Comment